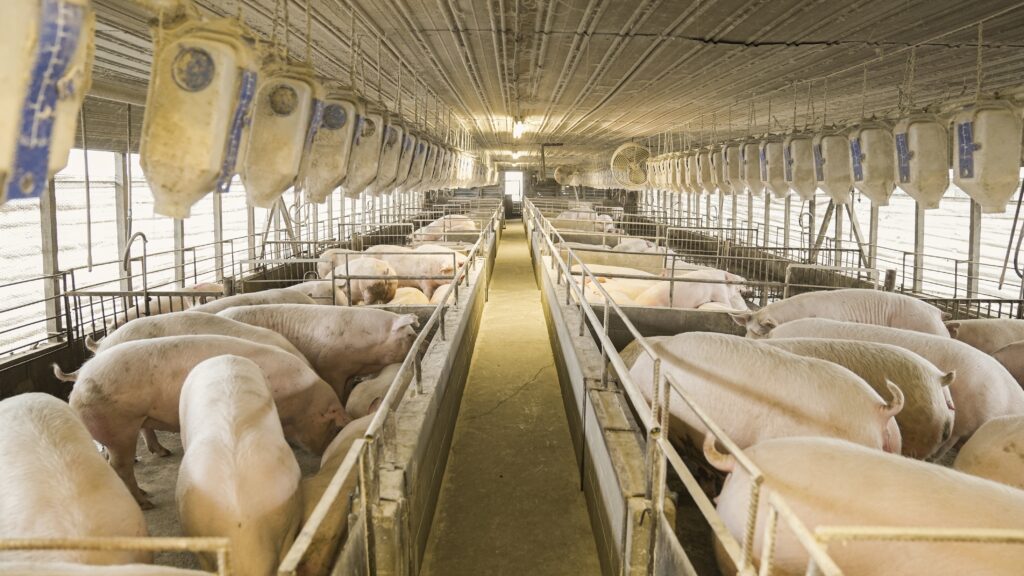

After considering a constitutional challenge to a California ballot initiative regulating space requirements for farm animals, the Supreme Court of the United States (“SCOTUS”) ruled on May 11th in favor of the state of California, allowing the law to stand. The proposal, known as “Prop 12,” set conditions on the sale of pork meat in California- regardless of where it was produced. It required, among other things, that all products be from pigs born to a sow housed in at least 24 square feet of space. This effectively imposed Prop 12’s animal housing standards on any producer, no matter the location, who wished to sell products to residents of California. This part of the law was promptly challenged and eventually heard by the Supreme Court.

The case, National Pork Producers Council v. Ross (“NPPC”) considered whether Prop 12’s regulation of the out-of-state production of products to be sold within state boundaries is a permitted action under a legal doctrine known as the dormant Commerce Clause. In other words, under what circumstances can a state government pass laws that primarily affect the actions of people in other states? SCOTUS agreed to consider the case, and oral arguments were heard last October. Many of the arguments centered on whether the law met the provisions of the “Pike balancing test,” which compares local benefits of a law to the burden that it places on out-of-state commerce to determine if the burden is clearly excessive.

NPPC Ruling

While parts of this ruling were agreed upon by all justices, the foundational legal analysis was a split decision, with several justices agreeing and disagreeing as to various parts. Ultimately, a plurality of the court held that Prop 12 was constitutional and enforceable by California. A minority of justices would have sent the case back to the district court for further consideration. The opinion of the Court (joined by the largest number of justices), was written by Justice Gorsuch.

In the initial, unanimously agreed upon, sections of the opinion, Gorsuch focuses on the “antidiscrimination principle” that “lies at the ‘very core’” of dormant commerce clause jurisprudence. In the clearest situations, this happens if a state set different standards for out-of-state businesses vs in-state businesses (for example, if Prop 12 had required Kansas producers to give pigs more space, but allowed California producers to confine animals in smaller pens). However, Gorsuch does not apply this principle, instead pointing to a concession by the Pork Producers Council that producers are treated similarly regardless of geography. Gorsuch then moves on to consider the constitutionality of a law that is not facially discriminatory (as in the hypothetical example above), but has a disproportionate effect on out-of-state businesses. While the court did not specify whether Prop 12 would fall into this category, it would have ultimately made no difference. Gorsuch refused to find such a law unconstitutional, writing that “[i]n our interconnected national marketplace, many (maybe most) state laws have the ‘practical effect of controlling’ extraterritorial; behavior.”

Next, Gorsuch considers the Pike balancing test in a series of sections where some justices join in his analysis while others do not. Pike asks the court to weigh local benefits of a law against the burden it places on out-of-state commerce. Again, Gorsuch returns to what he sees as an underlying requirement of discriminatory intent, even in the cases decided using the Pike analysis. He rules, in a section joined by Justice Thomas and Justice Barrett, that the cost/benefit analysis that Plaintiffs argued was not an integral part of the original Pike analysis, and that Pike does not authorize judges to “strike down duly enacted state laws… based on nothing more than their own assessment of the relevant law’s ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’”. He further highlights the perceived difficulty in doing so as a judicial body; “[h]ow is a court supposed to compare or weigh economic costs (to some) against noneconomic benefits (to others)? No neutral legal rule guides the way. The competing goods before us are insusceptible to resolution by reference to any judicial principle.” Instead, he disclaims that cost/benefit role, arguing that the responsibility is better given to those with “the power to adopt federal legislation that may preempt conflicting state laws.”

Gorsuch also considers a framing of Pike that “requires a plaintiff to plead facts plausibly showing that the challenged law imposes ‘substantial burdens’ on interstate commerce before a court may assess the law’s competing benefits or weigh the two sides against each other.” In a section joined by Justices Thomas, Sotomayor and Kagan, Gorsuch finds that under the facts presented in the complaint, a “substantial harm to interstate commerce remains nothing more than a speculative possibility.”

It’s important to note that the sections of the opinion addressing the Pike test were not adopted by the majority. While Gorsuch wrote the opinion of the court, his reasoning was not adopted by the entire bench. In fact, several justices (Sotomayor, joined by Kagan and Roberts, joined by Alito, Kavanaugh & Jackson) also wrote or signed onto dissents outlining their disagreements with specific elements of Gorsuch’s reasoning. These justices agree that courts can still consider Pike claims and balance a law’s economic burdens against its noneconomic benefits, even if the challengers do not argue that the law has a discriminatory purpose. Much like the Rapanos case of WOTUS fame, this case did not result in clearly defined legal doctrine.

Justice Kavanaugh wrote as well, concurring in part and dissenting in part. He highlighted concerns about the constitutionality of statutes like Prop 12, “not only under the Commerce Clause, but also under the Import-Export Clause, the Privileges and Immunities Clause, and the Full Faith and Credit Clause.”

NPPC: What Happens Next?

At least theoretically, other challenges to Prop 12 might be filed on dormant Commerce Clause grounds with more facts presented in the complaint. This would be possible because a plurality of Justices agreed that the Plaintiffs did not allege facts that would constitute a “substantial harm”. New complaints, however, might allege facts sufficient to meet that burden. Those hypothetical challenges may or may not also include some of the additional legal grounds identified in Kavanaugh’s opinion. But as of right now- and for the foreseeable future- Prop 12 is constitutional. However, there are other court cases pending that impact the immediate enforceability of Prop 12 and similar laws.

Enforceability

In California Hispanic Chamber of Commerce v. Ross, retailers asked for an extension of time to come into compliance with Prop 12 regulations for the sale of pork, which was granted by the court. For retailers selling “whole pork meat,” the regulations may not be enforced until July 1, 2023. For retailers selling veal and egg products, the regulations are currently effective.

Massachusetts Restaurant Association v. Healey addresses a 2016 Massachusetts law, similar to Prop 12. The language of the statute is available here, and the regulations are available here. The MA law was challenged on dormant Commerce Clause grounds, and the parties agreed to prevent enforcement of the portions of the law relevant to the sale of pork products until 30 days after the NPPC decision was issued by the USSC. The portions relevant to the sale of egg and veal products are currently effective.

To read previous NALC updates about Prop 12 cases, click here and here.

For information on state laws governing farm animal confinement, click here.