Earlier this year, the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) altered a central component of the Clean Water Act (“CWA”) by once again redefining the term “waters of the United States” (“WOTUS”). The term is a key aspect of the CWA because it determines which waterbodies are covered by the statute and which are not.

The CWA was passed in 1972, and prohibits “the discharge of any pollutant,” without a permit. The Act defines “discharge of a pollutant” as “any addition of any pollutant into navigable waters from any point source,” and in turn defines “navigable waters” as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.” Therefore, a person who discharges a pollutant into a water of the United States, or WOTUS, is in violation of the CWA unless they have a valid permit. Accordingly, CWA compliance hinges on knowing what does and does not qualify as a WOTUS. Instead of defining WOTUS within the text of the CWA, Congress passed that responsibility to EPA as part of the agency’s authority to implement the statute. Defining the term “WOTUS” has proven to be a challenge, and it has been redefined multiple times, leading to confusing jurisdictional differences.

Prior to the change earlier this year, the most recent attempt to define WOTUS came in 2015 when EPA, under the Obama administration launched a new rule that attempted to interpret the term. However, the 2015 rule was controversial and lead to a jurisdictional divide as some courts prevented the rule from being implemented in their jurisdiction while others allowed the rule to take effect. Under the Trump administration, EPA published a final rule in October, 2019 that repealed the 2015 rule. Scheduled to become effective December 23, 2019, the new rule is meant to reinstate the pre-2015 definition of WOTUS. The repeal is the first step in EPA’s two-part plan to redefine WOTUS. Sometime in 2020, the agency is expected to implement a new rule to replace both the 2015 and pre-2015 definitions of WOTUS.

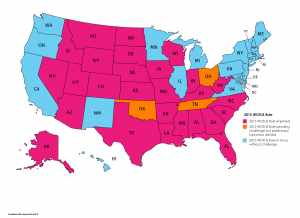

At this moment, the patchwork of regulation that resulted out of litigation over the 2015 rule will remain in place. Unless injunctions are issued in currently pending lawsuits against the October 2019 final rule, the October 2019 rule will be applicable everywhere on December 2, 20193. However, as late as August, 2019, courts were issuing opinions in on-going litigations over the validity of the 2015 rule. Before the repeal of the 2015 rule was announced, 22 states and the District of Columbia applied the 2015 rule, while 28 states applied the pre-2015 rule.

The first court order preventing the 2015 rule from taking effect was issued in August, 2015. The decision, State of North Dakota v. U.S. EPA, 127 F. Supp. 3d 1047 (D. N.D. 2015), applied to thirteen states: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Idaho, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming. The court granted the request by the states to prevent the implementation of the 2015 rule because it found that the underlying lawsuit challenging the validity of the rule was likely to be successful. That order remains in place, and now covers fourteen states after Iowa joined the lawsuit in 2018.

Later in 2015, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit issued a nationwide stay of the 2015 rule while courts figured out whether or not the rule was valid. The decision, In re EPA, 803 F.3d 804 (6th Cir. 2015) prevented the 2015 rule from taking effect across the nation until the Supreme Court overturned the decision in 2018. Following the reversal of the Sixth Circuit stay, the 2015 once again became effective in all states except for the thirteen states covered by the original order in, State of North Dakota v. U.S. EPA.

Since the Supreme Court overturned the Sixth Circuit opinion, several lawsuits challenging the validity of the 2015 rule and seeking an injunctive order preventing the rule from becoming effective while the litigation was on-going have been revived. Though several had begun prior to the Sixth Circuit decision, they had been put on hold after the nationwide stay. Following the reversal of the stay, the cases were reopened. In State of Ohio v. U.S. EPA, No. 2:15-cv-2467 (S.D. Ohio Mar. 25, 2019), the court refused to prevent the 2015 rule from being implemented in Ohio, Tennessee, and Michigan, concluding that the rule would be effective while the litigation challenging its validity was on-going. In State of Texas v. U.S. EPA, No. 3:15-cv-00162 (S.D. Tex. May 28, 2019), the court ordered that the 2015 rule be sent back to EPA for re-drafting to better comply with the CWA. The court also kept in place an order it issued in 2018 that prevented the 2015 from being implemented in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. A day after the decision was issued in State of Texas v. U.S. EPA, the court in State of Oklahoma v. U.S. EPA, No. 4:15-cv-00381 (May 29, 2019) concluded that it would not prevent the 2015 rule from being implemented in Oklahoma while the litigation challenging the rule was on-going. Finally, in State of Georgia v. Wheeler, No. 2:15-cv-00079 (S.D. Ga. Aug. 21, 2019), the court concluded that the 2015 rule violated the CWA and ordered that the rule be sent back to EPA for redrafting. Additionally, the court kept in place an order keeping the 2015 rule from becoming effective in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Currently, a little over half the jurisdictions in the United States apply the pre-2015 WOTUS rule while the rest apply the 2015 rule. Assuming the repeal of the 2015 rule takes effect on December 23, 2019, all jurisdictions will be required to apply the pre-2015 rule until EPA publishes its new WOTUS rule, anticipated sometime in 2020.

However, lawsuits have already been filed challenging EPA’s October 2019 repeal of the 2015 rule. A suit brought by the New Mexico Cattle Grower’s Association argues that EPA cannot revert to the pre-2015 WOTUS regulations because those regulations violate the text of the CWA by regulating interstate waterbodies and certain wetlands. A second suit, brought by the Southern Environmental Law Center and ten other environmental groups, challenges the repeal itself as invalid. Depending on how those cases progress, the repeal of the 2015 rule may be prevented from becoming effective in certain jurisdictions.

In short, the foundational definition determining who must comply with a major federal environmental statute, the CWA, is not well defined. It hasn’t been since the beginning, and competing definitions remain today. While several presidential administrations, including the past two, have attempted to bring clarity to the compliance requirements, it doesn’t look like that will happen anytime in the near future.

This map illustrates the patchwork of regulation that currently exists. The states in pink have enjoined the 2015 rule and follow the pre-2015 regulations. The states in blue follow the 2015 rule. The states in orange have on-going litigation challenging the 2015 rule, but have denied requests to enjoin the rule and therefore still apply the 2015 WOTUS definition.

To read the full decision in State of North Dakota v. U.S. EPA, click here.

To read the full decision in In re EPA, click here.

To read the full decision in State of Ohio v. U.S. EPA, click here.

To read the full decision in State of Texas v. U.S. EPA, click here.

To read the full decision in State of Oklahoma v. U.S. EPA, click here.

To read the full decision in State of Georgia v. Wheeler, click here.

To read the complaint filed by the New Mexico Cattle Grower’s Association, click here.

To read the complaint filed by the Southern Environmental Law Center, click here.

To read the 2015 rule, click here.

To read the 2019 repeal of the 2015 rule, click here.

To read about EPA’s two-step rulemaking process, click here.

To read the text of the Clean Water Act, click here.

To learn more about the Clean Water Act, click here.