In 2018, California passed Proposition 12, a high-profile ballot initiative regulating the production and sale of many veal, egg, and pork products. While “Prop 12” had some unique components, it was the latest in a series of farm animal confinement laws that had been passed across the United States since 2002. In the early stages, these laws included enhanced space requirements for certain farm animals (some combination of egg-laying hens, veal calves and breeding pigs) living within that state’s boundaries.

requirements for certain farm animals (some combination of egg-laying hens, veal calves and breeding pigs) living within that state’s boundaries.

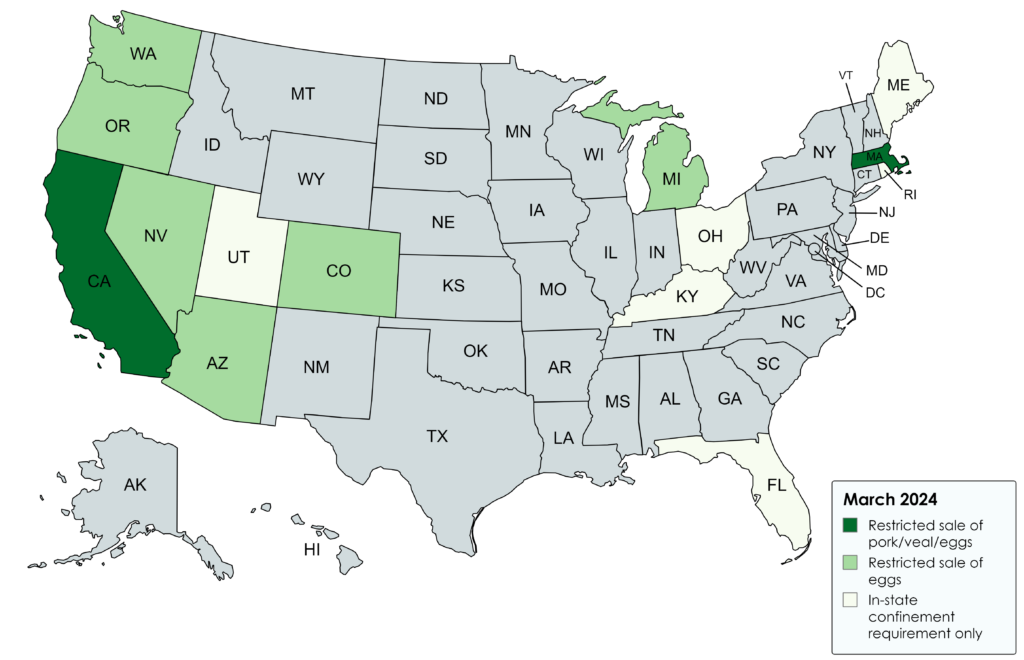

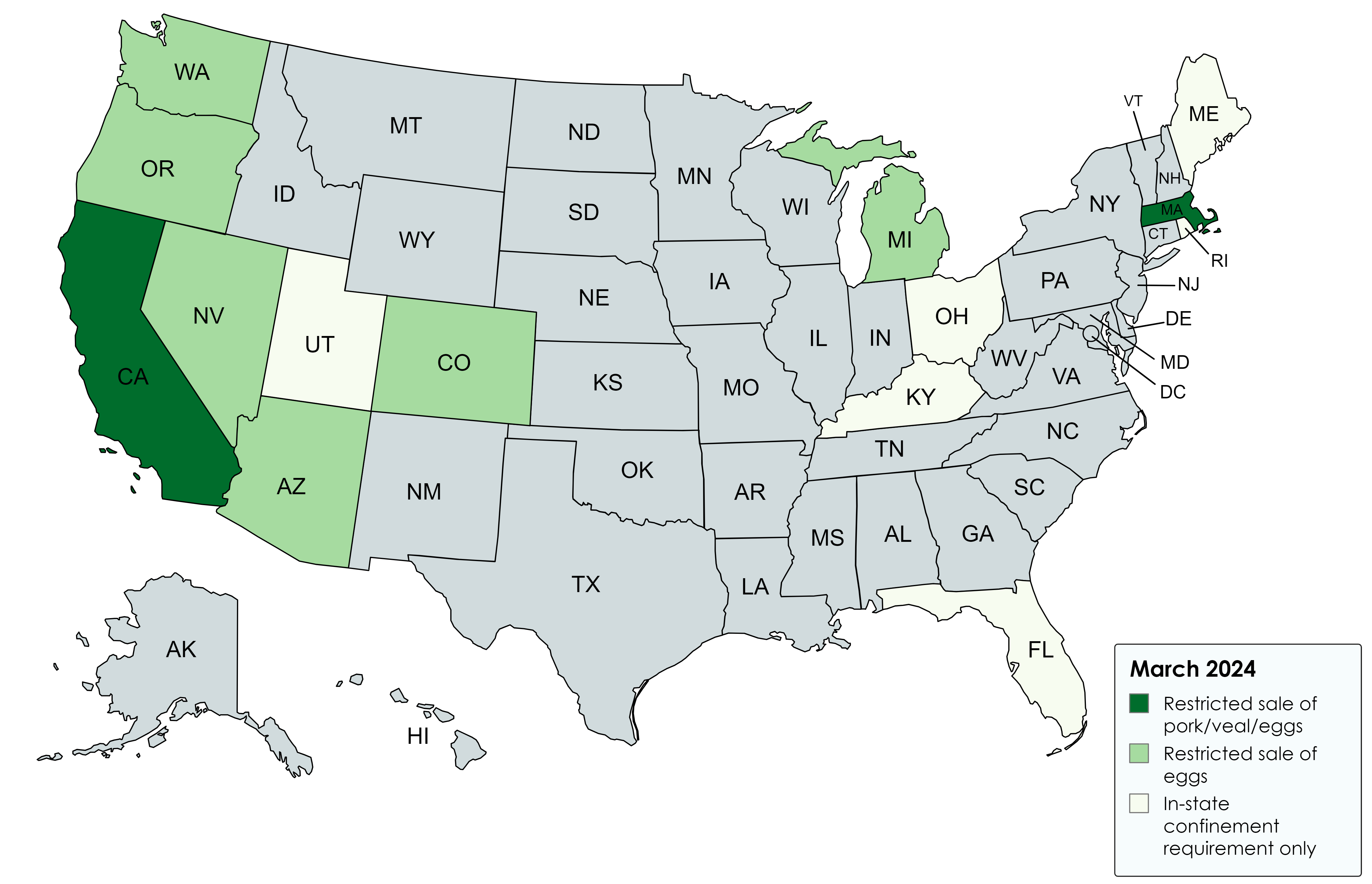

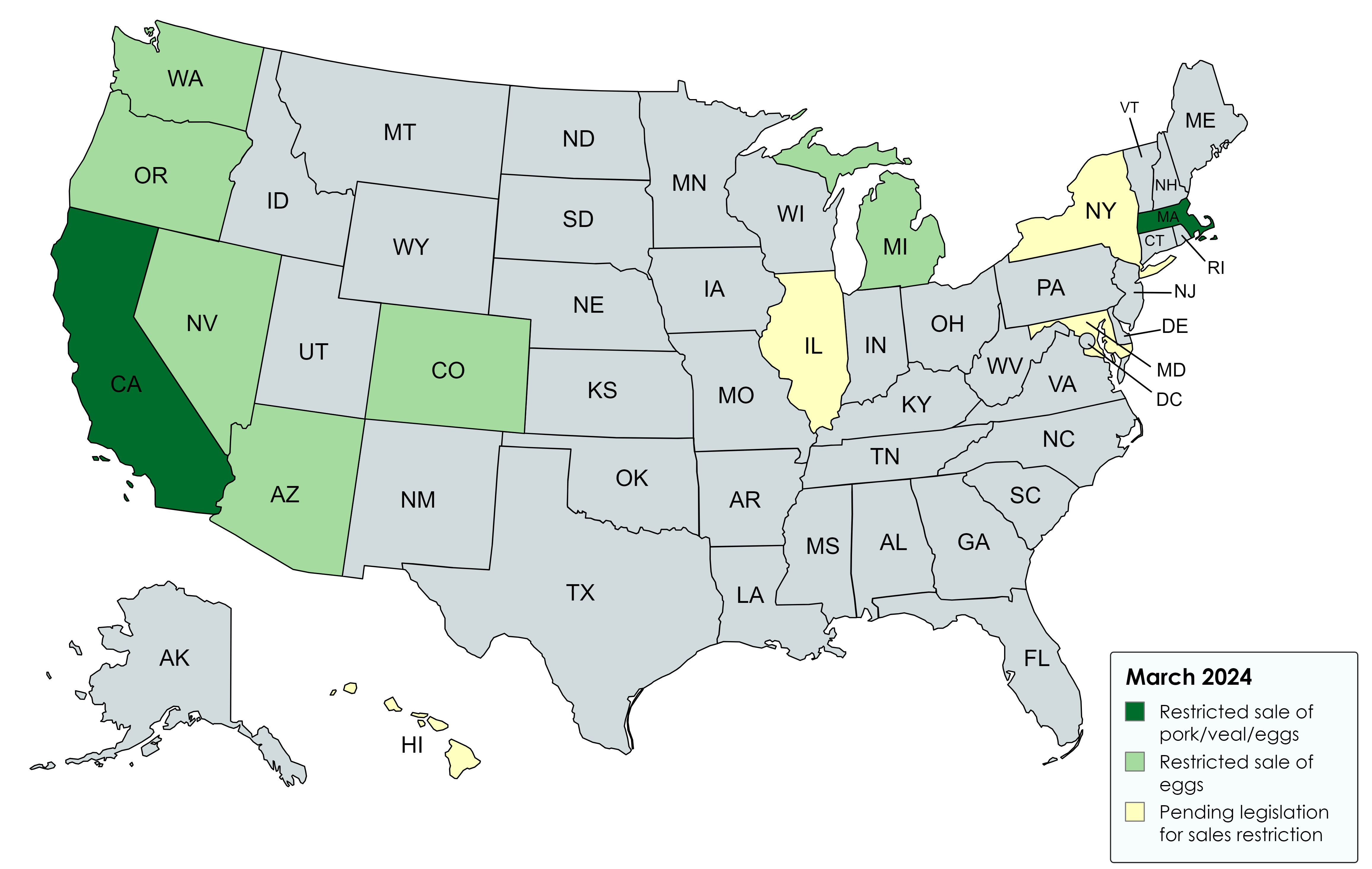

More recent iterations (including Prop 12) include space requirements for in-state production, but take it a step further, requiring that products sold within the state be traceable to animals living in similarly sized areas. These secondary statutes effectively impose that state’s animal housing standards on all producers, no matter the location, who plan to sell their products within the state’s boundaries.

Shortly after passage, Prop 12 was challenged in a case titled National Pork Producers Council et al v. Ross et al (“NPPC”) that made its way to the United States Supreme Court. In May 2023, SCOTUS decided in favor of the state of California, allowing Prop 12 to go into effect as written. (NALC explainer here).

That decision, while answering the immediate question of whether Prop 12 was enforceable, has not ended the discussion about laws regulating living conditions for farm animals. This post will discuss current events in this area, specifically; a challenge to a similar law in Massachusetts, another ongoing challenge to Prop 12, similar legislative proposals in other states, and federal proposals that would impact this issue.

Triumph Foods, LLC et al v. Campbell et al, 1:23-cv-11671

In 2016, voters in Massachusetts passed a ballot initiative called Question 3 (“Q3”). Similar to California’s enactment, it included components prohibiting both the actual confinement of the animal and the sale of non-compliant products within the state. The language of the statute is available here, the regulations are available here, and a FAQ by the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources is here. The provisions covering egg and veal products became effective in August of 2022. The provisions affecting the sale of pork products were postponed until after SCOTUS made its decision, ultimately becoming effective a year later, in August of 2023.

The pork provisions of Q3 were challenged by several out of state processors (NALC explainer here), who argued that the differences between Q3 and Prop 12 were enough to distinguish the two statutes so that the SCOTUS ruling would not force dismissal of the claims. Several of the arguments in the complaint were dismissed, but the commerce clause claims remained.

On Feb 5, 2024, the court ruled that a portion of Q3 was unconstitutional. Specifically, the unconstitutional portion of the act excluded mandatory compliance in situations where the buyer took physical possession of products at federally inspected establishments located in Massachusetts. As explained in the ruling, “The slaughterhouse exception has a discriminatory effect. The only way [plaintiffs] would be able to take advantage of the slaughterhouse exception would be to open its own federally inspected facility within the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which the Supreme Court has held violates the Commerce Clause.” Because it is discriminatory to out-of-state processors vs. in-state processors, and the state failed to demonstrate that the exception was passed for a legitimate local purpose, the court found that section to be unconstitutional. The court was then able to “sever” that portion of the law, which allowed for continued enforcement of the remaining sections.

However, in doing so the court decided to reconsider a claim that had been included in the original complaint, but had previously been dismissed. Specifically, he gave the plaintiffs the opportunity to submit a motion for summary judgment on the grounds that, without the severed provision, Q3 was preempted by the Federal Meat Inspection Act (“FMIA”). Preemption occurs when state laws conflict or interfere with federal laws. In these situations, the state law is invalidated by federal law, and can no longer be enforced. (NALC preemption explainer here).

On 3/6/24, plaintiffs submitted a motion for summary judgment. They argued, as expected, that Q3 was expressly preempted by the FMIA because it imposes additional conditions on facilities regulated under the FMIA. Further, plaintiffs argued that it was preempted because it conflicts with the objectives of the FMIA. Attorneys for the state of Massachusetts have until April 5 to file their response.

Iowa Pork Producers Association v. Rob Bonta, et al, 22-55336

While SCOTUS has already ruled that Prop 12 is constitutional based on the argument that it was not overtly discriminatory against out of state production but that it had a disproportionate impact on out of state businesses, another commerce-clause-based challenge is currently pending in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The case, Iowa Pork Producers Association v. Rob Bonta, et al, (“Bonta”) was dismissed by the District Court on Feb 28, 2022- before the SCOTUS arguments took place in NPPC. After plaintiffs appealed the dismissal, the case was stayed (or paused) until the NPPC case was heard and the decision published. The stay was since lifted, and the case has been briefed and advanced to oral arguments.

In terms of the commerce clause, plaintiff’s arguments are twofold. The first argument was not raised in the NPPC case. As explained in the NPPC decision, “under this Court’s dormant Commerce Clause decisions, no State may use its laws to discriminate purposefully against out-of-state economic interests. But the pork producers do not suggest that California’s law offends this principle.” However, plaintiffs in Bonta do argue that in-state and out-of-state producers are treated differently. The foundation for this argument traces back to Proposition 2, California’s original farm animal confinement law, passed in 2008, that eliminated the use of gestation crates for in-state producers. As outlined in the plaintiff’s brief, while “Proposition 2 allowed instate producers six years to comply with its provisions (November 4, 2008, to January 1, 2015), Proposition 12 was designed to take effect for out-of-state producers immediately. The turnaround requirements were to take effect on December 19, 2018—giving out-of-state producers a mere six weeks to come into compliance (as opposed to the prior five-year benefit provided to in-state producers).” Plaintiff brief. The discrepancy in the amount of time given to in-state versus out-of-state producers to adopt the “financial and operational burden[s]” of making the change establishes unconstitutional discrimination, according to the plaintiffs. Attorneys for the state of California disagree, arguing that Prop 12 is neutral in language and effect, because it “draws no distinction between in-state and out-of-state business owners or operators with respect to what pork products may be sold in California.” Answer brief (State of CA).

Plaintiffs also argued that Prop 12 violated the commerce clause because it has a disproportionate effect on out of state businesses. This was the central issue in NPPC, where the court found that it does not. (NALC explainer here). Plaintiff attempts to distinguish, or separate, itself from the NPPC ruling by claiming that the justices did not have enough information to show that effect was disproportionate. “Unlike the NPPC v. Ross opinion, which arose only from the context of a motion to dismiss, this Court has a full preliminary injunction record replete with evidence that Proposition 12 constitutes a federal regulation on pork production[.]” Given the additional information, plaintiffs argue, they are able to show the disproportionate effect that the NPPC plaintiffs could not. California, in response, argued that the NPPC decision answered this question in full, when the “Supreme Court considered virtually identical allegations of harm to out-of-state interests in National Pork and held that they did not suffice to state a Pike claim.” A brief submitted by Humane Society of the United States, who has joined the case as an intervenor/defendant, agrees with California in effect, but argued instead that the additional information was not relevant because SCOTUS ruled that Pike was not applicable in this situation. Answer brief (HSUS).

Plaintiffs in this case also make several other (non-commerce clause) arguments. They argue that Prop 12 violates due process protections because it is unconstitutionally vague and the language defining the action of “engaging” in a “sale” is unclear enough that it could extend to an indeterminable number of points throughout the supply chain. Both the state of California and HSUS disagree, arguing instead that it provides sufficient notice as to what the statute prohibits.

Finally, the plaintiffs argues on procedural grounds that the district court erred in dismissing the original claims by failing to apply the correct standard of review and not giving credit to allegations contained in the original complaint.

Oral arguments in this case were held on on January 9 of this year in front of three judges in the Ninth Circuit. A decision is pending.

State proposals

Given the SCOTUS ruling permitting California to enforce Prop 12 sales restrictions, several other states have similar pending legislation that would allow for sales restrictions within their borders. Hawaii, Illinois, and Maryland all have bills that would prohibit the sale of eggs from laying hens in cage production systems. New York has proposed legislation similar to Prop 12 and Q3 in that it would require specific living conditions for laying hens, breeding pigs and veal calves, as well as prohibiting the sale of products from animals raised in non-compliant conditions.

Federal proposals

At this time, there are two federal proposals that would limit the ability of states to place additional conditions on the sale of products within their boundaries.

The first is the Ending Agricultural Trade Suppression Act, or “EATS Act”. It has been proposed in the Senate by Sen Roger Marshall (R-KS), and cosponsored by 14 Republican colleagues. The House version was proposed by Rep. Ashley Hinson (R-IA), and cosponsored by 36 Republican colleagues. If passed, these bills would prohibit state governments from imposing standards or conditions on preharvest production of ag products if the production occurred in different state and the standard is different than that imposed by the other state. If there are no previously set standards in the state of production, then no standards may be imposed. In terms of enforcement, the EATS Act includes a private right of action for a wide range of people along the supply chain; from producers to laborers, trade associations and transporters. It also included preliminary injunction language that would order a court to issue a requested injunction unless the non-moving party- the government actor- proves that it is likely to prevail on the merits at trial and that issuance of the injunction would cause irreparable harm to the state or local government. This would reverse the burden of proof typically required to obtain a preliminary injunction, where the moving party (usually the plaintiff) has the responsibility of proving each requirement.

However, the EATS Act has met with significant opposition on the Hill. A series of letters opposing the proposal have been signed by over 200 members of Congress (both parties) and submitted to the chair and ranking member of the House (8/21/23; 10/5/23; 3/8/24) and Senate (8/29/23) Agriculture Committees. Further, the Harvard Animal Law & Policy Program published a report titled Legislative Analysis of S.2019 / H.R.4417: The “Ending Agricultural Trade Suppression Act” 118th Congress – 2023-2024 that raised concerns about both the language and the effect of the proposal. The report argued that significant numbers of laws affecting zoonotic diseases, plant/pest management, food safety and natural resources would also be affected, and that the proposal would result in extensive litigation, imposing costs on state/local governments and fed agencies. The EATS Act has been referred to both the Agriculture and the Judiciary committees, where it remains.

The other relevant proposal, S. 3382, was submitted by Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO). It is titled Protecting Interstate Commerce for Livestock Producers, and currently has no cosponsors. It is more limited than the EATS Act, with an application to “livestock and livestock-derived goods” rather than the broader “agricultural products.” If passed, it would prevent state and local entities from regulating the production, raising or importation of livestock and livestock-derived goods from other states if those regulations go beyond that which were imposed by the state of production. However, there would be exceptions so that states could regulate imports in the event of animal disease. S. 3382 also includes a private right of action, but does not include the language shifting the burden in the case of a request for a preliminary injunction that was included in the EATS Act.

While no other proposals have been formally introduced, several members of Congress have expressed interest in regulating this area of law.