Biotechnology – An Overview

Background

A uniformly accepted definition of biotechnology does not exist. The broadest definition includes any use of biological sciences to develop products and all conventional plant or animal breeding techniques. In the media, biotechnology generally means newly developed scientific methods used to create products by altering the genetic makeup of organisms and producing unique individuals or traits that are not easily obtained through conventional breeding techniques. These products are often referred to as transgenic, bioengineered, or genetically modified because they contain foreign genetic material. Agriculture is one of the first industries radically affected by biotechnology on both a legal and fundamental production level.

Biotechnology’s vast array of products impacts agriculture in a multitude of ways. Cattle hormones produced in bacteria are used to increase milk production in dairy cows. Genetically modified plants that express herbicide tolerance can survive applications that would otherwise kill their unmodified counterparts. Genetically modified tomatoes that resist bruising during shipment are allowed to ripen on the vine. Genetically modified corn plants produce plastic precursors which decreases the plastics industries’ need for petroleum. Genetically modified rice known as “Golden Rice” produces high levels of vitamin A that may enable third world countries to prevent blindness in children. Genetically modified cotton plants, known as “Bt Cotton,” produce a bacterial toxin that acts as its own built-in insecticide.

Producing meat and poultry food products by growing cells of livestock or poultry in a bioreactor and harvesting those cells to make food – a practice known as “cellular agriculture.” Farm-raised salmon grow twice as fast as their wild counterparts. Biotechnology companies indicate that this list is only the beginning and that the possibilities are limited only by imagination.

However, biotechnology consumer acceptance varies globally. The relatively recent development of this technology has presented novel legal issues for both private parties and governments. To solve this, the law attempts to keep pace with scientific advancement through regulation, assignment of liability, protection of intellectual property rights, and international dispute resolution. The limitless possibilities and exotic combinations of organisms pose a remarkable challenge for law and policy makers.

Federal Regulatory Authority

In biotechnology, administrative agencies such as the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have been given authority by Congress to create regulations implementing the requirements of the federal law. In 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States issued two rulings that are expected to have a major impact on how judges decide cases challenging those regulations and that agency authority.

Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, 144 S. Ct. 2244 (2024) overruled the long-standing doctrine of deference established in Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984). Chevron deference was a two-step process that clarified how and when federal courts should defer to an agency regulation interpreting a statute. Chevron is only applied in situations where a court had determined that the statutory language the agency was interpreting was ambiguous. If the language was ambiguous, the court would consider whether the agency’s interpretation of the statute was “reasonable”. If it was reasonable, the court was required to defer to the agency’s interpretation. If it was not reasonable, the court would overrule the interpretation.

Loper Bright formally overturned Chevron. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court held that “courts may not defer to an agency interpretation of the law simply because a statute is ambiguous[.]” This means courts now interpret statutes independently. They no longer automatically defer to how federal agencies read those laws. Following the Loper Bright ruling, courts are now required to exercise independent judgment in determining whether an administrative agency has acted within its statutory authority (the legal power granted by Congress). Courts may still seek guidance from the agencies involved, but courts will no longer be required to defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute.

In Corner Post, Inc. v. Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., 144 S. Ct. 2440 (2024), the Supreme Court extended the period during which a party may file a lawsuit challenging federal agency actions. According to 28 U.S.C.S. § 2401(a), the six-year statute of limitations began to run when an administrative agency’s action was “final.” In Corner Post, the Supreme Court ruled that an action becomes “final” when a plaintiff suffers an injury, rather than when a “final regulation” is released. This ruling expands the potential for plaintiffs to challenge federal agency rules and regulations that have been final for over six years.

While the full effect of these two rulings remains to be seen, it is highly likely that the agricultural industry will be impacted by the Supreme Court’s decisions. Importantly, the rulings fundamentally change how courts will resolve lawsuits challenging agency regulations for misinterpreting the agency’s statutory authority. Impacts are most likely to be felt in areas of the law, such as biotechnology, dominated by statutes with relatively ambiguous language where Congress has relied on agency regulations to fill in specifics.

Regulation

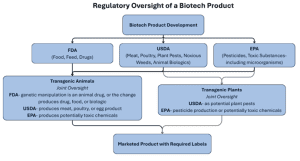

Under the Coordinated Framework for Regulation of Biotechnology, the United States regulates biotechnology products by three agencies: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The FDA primarily regulates biotech products intended for human and animal consumption, the USDA handles plant and animal biologics, and the EPA regulates products that have an environmental impact such as pesticides and toxic substances.

Federal policy holds that biotechnology itself does not pose inherent risks; therefore, biotechnology products are regulated under existing laws in the same manner as non-biotechnology products. No specialized regulatory law or agency governs biotechnology products. Regulatory oversight depends on the product’s intended use and chemical composition. Due to their novel combination of traits, some products may require regulation under multiple agencies. Both the transgenic organism and the products produced from the transgenic organism may be regulated.

The flowchart below illustrates how the FDA, USDA, and EPA may share regulatory responsibility for genetically modified organisms and products from development to labeling.

FDA Regulation of Biotech Products

The FDA is responsible for regulation of food, feed, human and animal drugs. It also has jurisdiction over the preharvest phase of cell-cultured meat and poultry food products, during which livestock or poultry cells are collected and generally placed in a bioreactor to grow and multiply. This process of producing food products is accomplished by growing cells in vitro or in a controlled environment and harvesting those cells to make food.

Foods derived from transgenic animals (genetic modification) may also be regulated by the FDA under the theory that the genetic material is an animal drug. The FDA also regulates the drug, food, or biologic produced by the genetic change. Additionally, the FDA regulates whole foods, food additives, dietary supplements, and drugs obtained from transgenic plants.

USDA Jurisdiction Over Plants and Animals

The USDA oversees meat, poultry, and egg products, plant pests and noxious weeds, and animal biologics. Under the shared oversight for cell-cultured meat, agreed upon in 2019, the FDA has jurisdiction during the preharvest phase, which is when cells are collected and grown in a bioreactor. Jurisdiction transfers to the USDA during the postharvest phase, which occurs when the cells are removed from the controlled environment. USDA retains jurisdiction during the postharvest processing phase and labeling of the final cultured meat and poultry food products. Additionally, the USDA may regulate transgenic plants if they are considered potential plant pests, and transgenic animals if they produce a regulated meat, poultry, or egg product.

EPA Oversight of Biopesticides and Microbes

The EPA regulates pesticides, toxic substances, and certain genetically engineered plants that produce pesticidal properties such as Bt toxin. Transgenic organisms that produce pesticide and chemical products are also regulated by the EPA. If a transgenic plant or animal produces potentially toxic chemicals or toxic byproducts, those products may also be subject to EPA regulation. The EPA also has the ability to regulate microorganisms under its toxic substance authority.

United States regulation of biotechnology is a complex structure in which three agencies work together to regulate technology that did not exist when current regulatory laws were enacted. The current regulatory framework is largely untested and continues to evolve as new transgenic organisms and products are brought to market. The flow chart above illustrates how oversight may shift between agencies. The table below offers a side-by-side summary of each agency’s core responsibilities and biotech examples.

| Agency | Primary Responsibilities | Biotech Examples | Phase of Oversight |

| 🧪 FDA | -Regulates human and animal food safety

-Oversees human and animal drugs -Reviews food from genetically modified organisms -Oversees preharvest phase of cultured meat |

-Transgenic salmon for human consumption

-GM corn used in processed foods -Lab-grown meat cells before harvest |

Preharvest: safety of ingredients, drugs, and biotech-derived food |

| 🌱 USDA | -Regulates meat, poultry, and egg products

-Oversees plant health and animal biologics -Inspects labels for certain food products -Shares oversight of cultured meat |

-Label approval for GM chicken products

-Regulating GM crops as plant pests -Cultured meat postharvest labeling |

Postharvest: production, labeling, plant/animal health |

| ♻️ EPA | -Regulates pesticides and toxic substances

-Oversees environmental impacts of biotech crops -Evaluates bioengineered microbes and biopesticides |

-Bt corn (pesticide producing)

-Transgenic cotton with herbicide tolerance -GM microbes producing industrial enzymes |

Lifecycle: environmental release, pesticide traits, microbial safety |

The coordinated framework will continue to evolve as new products and technologies challenge the traditional lines of agency authorities.

Labeling

Labeling of genetically modified products in the U.S. is regulated by the FDA and USDA. The USDA also oversees the federal disclosure standard for bioengineered food.

Federally, the FDA and USDA have regulated genetically modified product labels. Both agencies examine whether a label is false or misleading, known as misbranding. The FDA is responsible for bioengineered human and animal food, drugs, and cosmetic products, and does not have the authority to pre-approve labels of these products. The USDA is responsible for inspecting labels of genetically modified meat, poultry, and egg products to verify they are not misleading. The USDA has pre-marketing authority on labels and requires manufacturers to submit labels for approval before the product enters commerce.

Labeling products modified by biotechnology was voluntary until Congress passed an Act stating otherwise. This Act required the USDA to create the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard (the Standard) to establish a national standard for bioengineered foods and preempt varying state laws on the issue. The Act defines a bioengineered food as a food “(A) that contains genetic material that has been modified through in vitro recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA—lab created DNA combining material from different sources) techniques; and (B) for which the modification could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature.” Essentially, bioengineered foods are modified using rDNA techniques that cannot be achieved through conventional breeding or in a natural setting. Based on this definition, the Standard creates labeling and record keeping requirements for bioengineered foods.

| Requirement | Applies To | Labeling Method | Exemptions |

| Disclosure of bioengineered (BE) products | Food manufacturers, importers, and retailers selling covered foods | Text, standardized BE symbol, QR code, or telephone/text message | Restaurants and similar retail food establishments; small food manufacturers |

| Recordkeeping for BE products | Entities handling foods on the USDA’s BE Food List or with actual knowledge of BE | Documentation must be maintained and available for USDA audit | Not required for products not on BE List and without actual BE knowledge |

| Label pre-approval | Only for USDA-regulated meat, poultry, and egg products | Labels must be submitted to USDA for pre-market approval | Not applicable to FDA-regulated products |

Under the Standard, a covered or regulated entity includes food manufacturers, importers, and retailers. Covered entities are required to make appropriate disclosures under the Standard and maintain appropriate records. The federal law allows parties to choose one of four labeling methods for their disclosure: text indicating the use of bioengineered products; the use of a standardized symbol; an electronic link or QR code; or a text or telephone number (depending on the product’s label size).

The USDA stated the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) will develop and maintain a list of bioengineered foods to identify the crops or foods that are available in a bioengineered form and for which regulated entities must maintain records. The AMS updates the List as necessary to reflect currently available bioengineered foods but at least on a yearly basis through appropriate notice and comment periods.

Noteworthy AMS List exclusions are enzymes, yeasts, and other microorganisms produced in controlled environments. If an entity has actual knowledge that these microorganisms or other foods included in their products are bioengineered, then disclosure and recordkeeping is required.

Regulated entities selling a food on the AMS List must maintain records on whether that food is bioengineered or not. For example, if a regulated entity sells alfalfa that is not bioengineered, the regulated entity must document that fact. In the same manner, if the regulated entity sells bioengineered alfalfa, they must maintain documentation showing the food is bioengineered. If the regulated entity is selling a food for which they have actual knowledge (confirmed knowledge, not assumed) that the food is bioengineered, the entity must maintain documentation of such even if it is not on the AMS List yet.

Starting January 1, 2022, covered entities became required to label products under the Standard. Prior to that date, covered entities could voluntarily place disclosures on product labels. Importantly, federal labeling laws and regulations preempt all state biotechnology labeling laws. This means state laws may not impose different or additional requirements that conflict with federal labeling laws and regulations. Previously, states like Connecticut, Maine, and Vermont enacted their own biotechnology labeling laws but now must follow the federal regulation standards. However, states may administer their own remedies for federal standard violations. The USDA relies on record-keeping and compliance-based enforcement rather than direct testing of bioengineered products.

The Standard has five important exemptions: 1) food served in a restaurant or similar retail food establishment; 2) very small food manufacturers; 3) foods with unintentional bioengineered ingredients under a presence threshold; 4) foods derived from animals that consumed bioengineered feed; and 5) foods certified under the USDA National Organic Program (NOP). Under 7 C.F.R. § 66.1, exempt restaurants and similar retail food establishments include a wide variety of venues including: planes, trains, food trucks, cafeterias, and bars, among others. A very small food manufacturer is exempt where the manufacturer has “annual receipts of less than $2,500,000.”

The Standard does not require disclosures for “food in which no ingredient intentionally contains a bioengineered (BE) substance, with an allowance for inadvertent or technically unavoidable BE presence of up to five percent (5%) for each ingredient.” The Standard also exempts foods that are derived from animals that are themselves not bioengineered, but that eat bioengineered feed. Lastly, the Standard exempts food products certified under the NOP as bioengineered foods cannot obtain certification under the NOP.

Liability

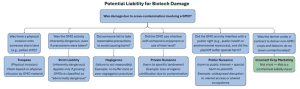

Biotechnology related damages are typically addressed using traditional common law tort theories. Damage from the use of biotechnology usually consists of contamination of non-genetically modified organisms by genetically modified ones. Biotechnology damage has the potential to fall under five different common law tort actions: trespass, strict liability, negligence, private and public nuisance. Farmers may also face contract-based liability for incorrect crop marketing.

One possible liability theory may be in an action for trespass. For example, if transgenic pollen moves from the field where it is produced onto another’s property, a physical invasion may occur. If this invasion results in damage, then an action for trespass may be an appropriate choice.

Strict liability may also be an avenue for the recovery of damages if a farmer is damaged by a neighbor’s transgenic crop. This recovery theory requires one important step: growing transgenic crops must be designated as an abnormally dangerous activity (inherently risky). Only then can the injured party recover despite precautions taken by the other party. However, demonstrating that raising transgenic crops is an abnormally dangerous activity is becoming more difficult with the widespread use of such crops.

Negligence is also a potential method of establishing liability. This would require that biotechnology companies and farmers using transgenic crops must take reasonable precautions to prevent damage to other parties. Then if entities fail to reasonably protect others from the risks associated with transgenic organisms, they may face negligence liability.

Private nuisance is also a theory that may be used to confer liability onto biotechnology users. Liability may arise if it can be shown that the use of transgenic organisms unreasonably interfered with the quiet use and enjoyment of a neighbor’s land and caused significant harm.

Another theory is public nuisance, which allows a private party to recover damages and to prevent further harm to the public. There is no requirement of distinct harm to land rights. To recover, the required harm is a demonstration of unreasonable interference to a right common to the public. To recover, the individual who pursues the action must have been damaged in a special manner distinct from the harm suffered by the general public and must prove that growing a particular transgenic crop interfered with a common to the general public.

These theories of liability attempt to use traditional common law causes of action on new and expanding technology. Liability for farmers may also potentially arise under biotechnology agreements and contracts. Most seed companies selling biotechnology seed require that farmers sign a technology agreement. These agreements often give seed company representatives the right to access farmers’ property for inspection, limit the ability of farmers to save seed, and control production practices involving the biotech seed. These biotechnology agreement terms may leave farmers open to liability for breach of contract if they fail to follow the agreement.

Another source of liability may be incorrect crop marketing. If a farmer is contracted to deliver crops free from biotechnology, failure to do so could lead to liability. Notably, farmers who certify their crop is biotechnology-free may still be liable due to contamination despite lack of control or knowledge of such contamination.

| Tort Theory | What it Means | Example |

| Negligence | Failure to take reasonable steps to prevent foreseeable harm | Farmer fails to plant buffer zone to contain genetically modified crops |

| Private Nuisance | Unreasonable interference with another’s use and enjoyment of their land | Biotech crop causes odor or disrupts pollination from adjacent farm |

| Public Nuisance | Interference with public rights that causes special harm to an individual | Widespread planting interferes with public ecosystem or access, and one farmer suffers economic harm |

| Strict Liability | Liability for inherently dangerous activities, even with precautions | Planting transgenic crops classified as abnormally dangerous under local laws |

| Trespass | Physical invasion of property | GMO pollen drifts onto neighboring organic field |

| Incorrect Crop Marketing*

*contract-based liability, not a tort theory |

Breach of contractual or sales representations regarding GMO content | Farmer certifies crops as GMO-free, but contamination of that crop occurs, breaching contract terms |

Intellectual Property

Legal protections such as patents and plant variety rights are key to the regulatory environment surrounding agricultural biotechnology. These protections are designed to encourage agricultural innovations by granting developers exclusive rights to their inventions. At the same time, they can influence how the new technology is used, including whether seeds can be saved or shared. Understanding how intellectual property works in the context of agricultural biotechnology is essential for navigating the development, regulation, and use of these products.

Intellectual property rights play a role in the growth of agricultural biotechnology. By granting exclusive rights to make, use, and sell new inventions, these legal protections help incentivize investments in research and development. Biotechnology research is expensive, but its products are lucrative. However, the technology itself is easily detected by scientific tests. These factors lead to a rapid expansion of intellectual property rights in biotechnology. In turn, the IP protections continue to shape how the new technologies are developed, accessed, and applied across the agricultural industry.

Until the Plant Patent Act of 1930 (PPA), living organisms were unpatentable because they are products of nature and therefore did not meet the requirements of utility patents. The PPA allows developers of new and distinct plants to prevent the asexual reproduction, sale, and use of patented plants. However, it does not protect sexually reproduced plants.

The Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970 (PVPA) provides protections to breeders who create new and distinct varieties of sexually produced plants. It prevents the unauthorized sale or growing of a protected plant. The PVPA protects both the plant and its seeds for twenty years. The PVPA also contains an exemption for farmers who save seed for their own use and an exemption for research using the protected plant.

In 1980, the Supreme Court decided that living organisms were patentable under general patent law if the organism met the patent requirements. This ruling resulted in patents both on the technology used to create transgenic organisms and the new organisms themselves. Varieties created with traditional breeding methods are also patentable.

In 1994, the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (UGAA), updated the validity term for utility patents. For patents filed on or after June 8, 1995, the term is twenty years from the earliest filing date. For utility patents filed before that date, the term is seventeen years from the issue date or twenty years from the earliest filing date, whichever is longer. Prior to the UGAA, the term was seventeen years. Utility patents restrict who can grow, sell, use, and manufacture protected biotech plants and. Unlike the PVPA, utility patents don’t allow for seed saving or research exemptions. Due to the elimination of the PVPA exemptions for their products, biotechnology companies are able to assure a greater return on their investment for transgenic research and development. This has fueled the biotechnology revolution in agriculture. Patent holders may allow others to use their protected process or product by granting a license.

Typically, when farmers buy transgenic seed, they are granted a license by the patent holders to use that seed on a limited basis in their farming operation. The technology agreements that farmers normally sign upon purchase of transgenic seed also contain provisions designed to protect the intellectual property rights of the patent holders.

Patents are issued on a national basis, and a patent must be obtained in each country where protection of the biotechnology product is sought. Generally, patent systems existed only in developed countries, but biotechnology has driven the development of patent law internationally in both developed and developing countries. The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) mandates that all countries of the World Trade Organization (WTO) develop patent or other intellectual property rights protection systems.

The spread of these systems has also caused debate about farmers’ rights. The debate is based on the idea that biotechnology companies are given free access to traditional plant varieties used and developed by farmers for generations. The farmers are then required to pay for the genetic modifications made to their traditional varieties without receiving any benefit from the basic genetic information that they provide to the biotech company.

| Feature | Plant Patent Act (PPA) | Plant Variety Protection Act (PVPA) | Utility Patent |

| Type of Protection | Patent | Certificate | Patent |

| Covers | Asexually reproduced plant varieties | Sexually reproduced plant varieties (and tubers) | Biotech traits, methods, organisms (including patents) |

| Term Length | 20 years from filing date (since 1995) | 20 years (25 years for trees/vines) | 20 years from filing date |

| Exemptions | No exemptions for research or saving seed | Farmer and researcher exemptions | No exemptions; stronger protection than PVPA |

| Requires Sexual or Asexual Reproduction? | Asexual reproduction (e.g., cuttings) | Sexual reproduction (via seed) | Both sexual and asexual can qualify |

| Governing Law | Plant Patent Act of 1930 | Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970 | General Patent Law (Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 1980) |

| Transferable by License? | Yes | Yes | Yes |

International Issues

In addition to the intellectual property issues, biotechnology has fueled numerous international disputes because different areas of the world vary in their level of acceptance of the technology. The European Union has used safety concerns to prevent importation of transgenic crops. Advocates of biotechnology allege that these concerns are not based on legitimate science and are an illegal trade barrier under World Trade Organization (WTO) Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Agreements. Other groups fear that biotechnology will damage the ecosystems of developing countries or that developing countries will be unable to pay for access to the technology that may benefit them most. Others argue that biotechnology is key to feeding the world’s hungry by developing high yielding crop varieties for all parts of the world, and that biotechnology benefits the environment.

The Codex Alimentarius Commission, administered by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), has established international guidelines for food safety and labeling of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The Codex’s guidelines are frequently referenced in WTO trade disputes. For example, in EC-Biotech (2006), the EU’s delay in approving genetically modified crops was challenged by the U.S., Argentina, and Canada at the WTO. The WTO panel found the delays violated trade obligation; however, no penalties were imposed on the EU.

The Codex’s guidelines also serve as a benchmark for evaluating whether national restrictions on GMOs are consistent with international trade obligations. As these disputes continue, biotechnology remains at the center of many evolving international legal, trade, and policy issues.

Definitions

Biotechnology Terms

- Bioengineered food: Food that contains genetic material altered through laboratory techniques not possible with traditional breeding.

- Cellular agriculture: The process of growing animal products like meat or dairy from cell cultures instead of whole animals.

- Genetically modified organism (GMO): A plant, animal, or microbe whose genetic material has been changed using modern biotechnology techniques.

- In vitro: Latin for “in glass”; refers to processes or reactions taking place in a lab environment outside a living organism; grown in lab conditions.

- Recombinant DNA (rDNA): A form of DNA that is created in a lab by combining genetic material from different sources.

- Transgenic organism: An organism that contains genes from a different species, introduced through genetic engineering.

Legal & Regulatory Terms

- Agency rulemaking: The process by which federal agencies create detailed regulations based on the authority granted to them by Congress.

- Chevron deference: A legal principle (now overturned) that required courts to defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute when the law was ambiguous.

- Loper Bright decision: A 2024 Supreme Court ruling that ended automatic judicial deference to agency interpretations of ambiguous laws.

- Statutory authority: The legal power given to a government agency by Congress to regulate certain issues.

- Technology agreement: A legal contract farmers sign when buying genetically modified seed, typically restricting seed saving and requiring specific farming practices; contract to use GMO seeds.

- Utility patent: A type of patent that protects inventions, including genetically engineered organisms, for a set period (usually 20 years from filing).

- PVPA (Plant Variety Protection Act): A U.S. law that gives intellectual property rights to breeders of new plant varieties that reproduce through seeds.

- Plant Patent Act (PPA): A law that protects new plant varieties that are reproduced asexually (not from seeds).

Regulatory & Scientific Terms

- Biologic: A medical product derived from living organisms, such as vaccines or gene therapies.

- Bioengineered food list: A list maintained by USDA of all foods that are known to be available in bioengineered form and require special recordkeeping.

- Bt toxin: Bacillus thuringiensis is a soil-dwelling bacterium that naturally produces a toxin fatal to certain herbivorous insects. The toxin, known as cry toxins, has been used as an insecticide spray since the 1920s and is commonly used in organic farming.

- Plant pest: An organism that harms plants or plant products; regulated by USDA when found in genetically modified organisms.

- Presence threshold: The maximum amount of a substance (like GMO ingredients) that may be unintentionally present in a food product before labeling is required; trace limit amount.

- Toxic substance: A chemical or compound that can cause harm to living organisms; regulated by the EPA.

International & Trade Terms

- Codex Alimentarius: A set of internationally recognized food standards and guidelines developed by the FAO and WHO to protect consumer health and promote fair trade.

- TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights): A WTO agreement requiring member countries to protect intellectual property rights, including patents on biotechnology.

- WTO (World Trade Organization): An international organization that regulates global trade and resolves trade disputes between member countries.